Data Analysis and the FLSA de Minimis Doctrine: Data and Technology Considerations for FLSA Litigation

By Joe Sremack, CFE, CISA, Partner, Advisory Services

On July 10, 2024, the U.S. Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals upheld the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) de minimis doctrine for overtime while preserving the triable issue of fact in Cadena v. Customer Connexx LLC. The FLSA de minimis doctrine for overtime—the principle that relieves employers from being required to pay for irregular, small, or difficult to capture work time—has been challenged numerous times. In the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals’ decision, the doctrine survives, but the court held that a triable issue of fact to determine whether the time in question is truly de minimis.

A broader scope of data and strategies is needed to navigate these complex FLSA cases, emphasizing the importance of comprehensive data analysis beyond traditional timekeeping systems. The expanded data points may help establish whether time not captured in the timekeeping system is irregular, small, or difficult to capture.

The FLSA de Minimis Rule: An Overview

The FLSA de minimis doctrine safeguards employers by recognizing that certain small amounts of time are too minimal to warrant compensation. However, determining what constitutes de minimis time can be complex and often hinges on a combination of data analysis, employee and employer depositions, and document review. Based on that information, attorneys must establish whether the time in question is truly insubstantial and irregular, typically falling into periods of a few minutes. This determination necessitates comprehensive data analysis and a deep understanding of legal precedents.

The de minimis doctrine was considered settled until Cadena v. Customer Connexx LLC. Several key rulings established that small amounts of time, such as computer boot-up and login time or the time between entering an employer’s building and the timekeeping system start time, did not require compensation. As a result of the Cadena v. Customer Connexx LLC decision, FLSA litigation regarding overtime pay may again require a deeper analysis of employee time beyond what is found in timekeeping systems.

Data Identification

Just as different state and federal laws require customized legal approaches, different organizations’ business operations require custom data approaches. The first step any party should take is to identify potentially relevant data sources based on the available information. Legal teams can identify data sources through client discussions, discovery, and public information. All three of these channels are typically considered during FLSA litigation, but the scope and approaches to these channels differ when de minimis issues are present.

For de minimis-related issues, legal teams should expand the scope of data beyond the timekeeping systems by including data responsive to questions about employee activity before, during, and after tracking on-the-clock time. This type of ideation and planning is a best practice in most data-intensive litigation but is not always considered in the context of FLSA and other types of wage and hour litigation. The approach involves mapping out standard and non-standard employee and employer behavior to identify the data types collected in the process and the corresponding data sources, such as a building security system that tracks employee badge-in and badge-out activity. Several frameworks and methodologies are available for this process, including design thinking and CRISP-DM.

The scope of systems and data sources vary based on the employer and the litigation. Several types of data sources to consider during the planning phase are:

| Data Source Type | Description |

|---|---|

| Timekeeping system | System of record for employee work start and end times, including breaks. |

| Work software | System used by employees to perform a work function (e.g., call logging, point-of-sale system, or inventory management). |

| Building access control systems | System that controls and logs individuals’ building access via security code, device, or biometrics. |

| Project management software | Software to track scheduling and assignments. |

| Workforce management software | Software to manage remote and mobile workforces (e.g., Deputy/Connecteam). |

| Accounting/ERP/HR systems | Software systems for tracking payroll and import of timekeeping details. |

| Enterprise communications | Email, instant messages, and collaboration software. |

| Expense management software | Software to track expenses submitted by employees. |

| Network activity logs | Logs from network usage (e.g., VPN) can track when employees are accessing work-related systems. |

| Mobile devices | Smartphones, wearables, and tablets. |

| Employee/manager workstations | Computers where work is performed to track device boot-up/login times and activities conducted outside of ‘worked hours.’ |

| CCTV | Feeds to determine typical time spent on work activities that may not be tracked. |

The decision to pursue specific data sources depends on the specifics of the business, the value and accessibility of the data, and the evidentiary value. The design thinking methodology is one approach for assessing the value of the data, which is achieved by formulating questions and determining whether the data may provide answers. These questions and an understanding of the business operations serve as guides to inform what types of data sources may be relevant. For de minimis issues, the foremost questions are based on the legal questions:

- Was the daily amount of time insignificant?

- What was the aggregate time period?

- Was the alleged de minimis time regular and recurring?

- Are there practical difficulties in capturing the time?

- Are there contextual considerations that are unique to this case?

The technologies involved also play a role in the data identification process. Not all data sources are readily accessible. Mobile devices and wearables require forensic collection; some cloud-based SaaS software do not have robust data export options; ERP systems require knowledgeable technical support to export, and in sensitive matters, ERP systems may require a forensic expert to extract the data correctly. In addition to accessibility, the data sources may or may not have the information that is required or expected.

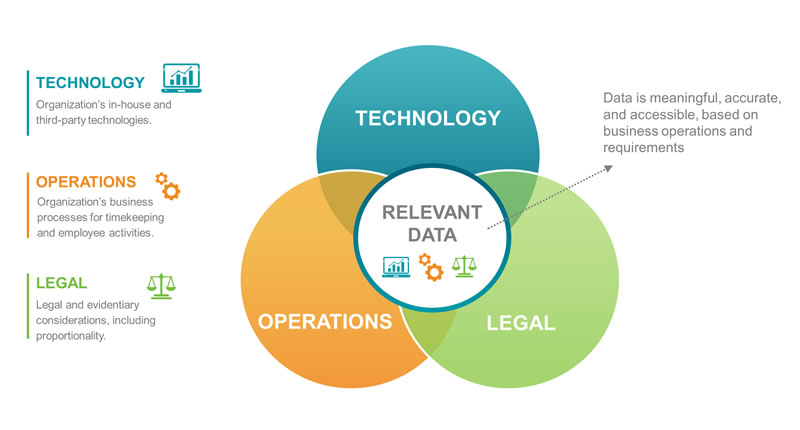

Figure 1 illustrates the interrelationship between the technology, operations, and legal factors that determine the relevant data sources.

Analysis Considerations

Analyzing employer and employee data to evaluate the de minimis threshold involves several potential areas of exploration. The first step is to utilize comprehensive data aggregation and standardization techniques. This consists of compiling the relevant data sources (e.g., timekeeping records, payroll data, and employee schedules) and standardizing them into a uniform format. This is performed through specialized database software and custom computer programming. This produces a database that allows for easier analysis of events by employee over time, with the data standardized across formats and timestamps to enable unified analysis.

Once the data is in a unified structure, statistical analysis is applied to determine whether the time in question qualifies as de minimis. This approach involves performing detailed time series analysis to identify patterns in the small work periods that are not captured in the timekeeping system data. The analysis can calculate the averages, variances, anomalies, and distributions of these short work periods and then determine whether the time represents a significant amount of work. This type of analysis can identify patterns to determine whether the time in question is truly minimal and irregular, determine duration to calculate the precise amount of time vis-à-vis the de minimis threshold and assess the frequency of these short periods of time to test whether that meets the de minimis threshold in aggregate. Additional analysis can be performed using machine learning across the unstructured data, such as communication data, to detect further patterns and variances.

Finally, qualitative analysis can be performed to further ground the findings in contextual facts, if available. The context of the de minimis time periods matters. Beyond just the contractual terms of employment agreements, de minimis time may be proven or disproven based on employee activity or business operations. Analysis of the time it takes to get to a workstation and log into the timekeeping system once the employee enters a building or work site can be quantified, and it can be further supported through analysis of communication data and traditional fact development. The administrative feasibility of capturing de minimis time can also be evaluated through expert witness system analysis.

Conclusion

The FLSA de minimis doctrine presents unique data challenges and opportunities that have survived but allow for triable issues of fact to be considered. Forensic data analytics techniques offer legal teams more sophisticated approaches to this type of case. The identification of potentially relevant sources remains a critical phase in discovery. Once the data is available, a host of analysis techniques can be applied to rapidly and reliably determine whether the de minimis doctrine applies. As technology continues to evolve, more data becomes available, and more avenues for exploration become available.

Looking for answers? We can help.

Marcum is a leading assurance, tax, and advisory firm with prominent professionals who bring decades of experience to help clients successfully navigate complex issues at the intersection of technology and litigation. We understand the challenges your team faces and support all phases of expert services, from forensic technology and data analytics to damages and statistical analysis. Contact us today to learn more.