The Infringer’s Profits: The Financial Expert as a Guide

By Roman Matatov, CPA, CFF, CVA, CFE, Cr.FA 1

Introduction

Monetary recovery in non-patent intellectual property (“IP”) disputes may be measured as the amount of profits realized by the infringer attributable to the alleged infringement. However, during a dispute, determining the amount of profits is subject to several challenges, including a rigorous analysis of the financial condition and performance of the infringer, and an understanding of the economic and competitive environment in which the infringer operates.

Monetary recovery in non-patent intellectual property (“IP”) disputes may be measured as the amount of profits realized by the infringer attributable to the alleged infringement. However, during a dispute, determining the amount of profits is subject to several challenges, including a rigorous analysis of the financial condition and performance of the infringer, and an understanding of the economic and competitive environment in which the infringer operates.

The retention of a financial expert as a guide, early in the adversarial process, is one way to address these challenges and could add tremendous value to counsel’s litigation strategy. A competent financial expert could promptly navigate through the myriad amounts of data produced, clearly and concisely evaluate the document production, and begin to efficiently determine the infringer’s profits, if any.

Revenues and Apportionment

One challenge faced by counsel is demonstrating the revenues related to the IP dispute. The analysis of infringer’s profits could begin by determining the revenues from the sale of products embodying the disputed IP; then determining the revenues from the sale of other products by the infringer; and then by apportioning these total revenues between those attributable to the disputed IP – the infringing revenues – and those not attributable.

The products sold, the length of time during which the sales occurred, the prices charged for the products during that period, and the geographic regions where the products were sold are some factors pertinent to the determination of the infringing revenues.

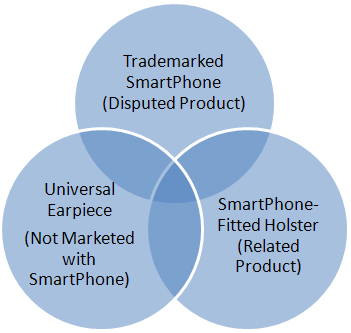

When addressing the products sold, the challenge includes determining whether it is one particular product, group of related products, or products not marketed or sold together by the infringer, which should form the basis for the profitability analysis. For example, if the subject of the dispute are smartphones bearing allegedly infringing trademarks, the financial expert’s analysis could consider the trademarked smartphone (the disputed product), the smartphone-fitted holster sold specifically with the disputed product (a related product), and an earpiece usable with many phones (a product not specifically marketed with the disputed product). As demonstrated below, these three types of products could each potentially be a component of the infringer’s profits analysis.

When addressing the length of time during which the sales occurred, the challenge includes reasonably estimating when the alleged infringement began, when and whether the infringement ended, and whether the infringement persisted continuously or intermittently. A detailed analysis of the underlying historical accounting data – such as sales journals, general ledgers, and inventory records – would provide evidence of sales of particular products during particular time periods.

Also of importance would be considering how and whether the prices charged for the products changed during the period of infringement. Further, based on the determination of geographic scope, the dispute may require the calculation of the infringing revenues in one or several countries – each a unique business environment necessitating a sufficient understanding of the varying economic landscapes within which the infringer operated.

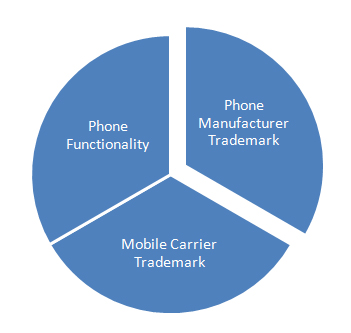

Another challenge is identifying, or apportioning, the amount of the infringer’s sales attributable to the alleged infringement. A product embodying the IP may also consist of other components. The revenues realized from the sale of the whole product should be apportioned between the IP in dispute and other components. For example, as demonstrated below in connection with the smartphone example presented in this article, the revenues could be apportioned between those attributable to the smartphone manufacturer trademark, to the mobile carrier trademark, and to the inherent phone functionality.

Underlying the various methods by which to empirically evidence and support apportionment is the concept of relative value – the value of the disputed IP relative to other components, elements, ingredients, or facets of the whole product. The failure to consider apportionment is a failure to relate the calculated monetary recovery to the alleged wrongdoing – the alleged infringement. Such a failure would be significant, as it would severely undermine the credibility of the financial expert, would make the profitability analysis of no use to the trier of fact, and could cause detriment to counsel’s litigation strategy.

Costs

Determining costs attributable to the infringing revenues is another challenge that IP counsel must understand and evaluate. The IP owner will naturally desire that fewer costs – and thus greater profits – be considered to be attributable, while the alleged infringer will argue that greater costs are attributable – and thus fewer profits. Because different legal jurisdictions and venues consider different costs as acceptable, having an understanding of how different costs can impact the profitability analysis is of utmost importance to counsel.

A financial expert could address this challenge of cost uncertainty by identifying various costs related to the infringing revenues and presenting the trier of fact and counsel with a matrix of costs. Generally, costs incurred in the course of making and selling the infringing products – i.e. the direct costs – are attributable to the infringing revenues. Certain fixed and administrative costs of the business may also be attributable to the infringing revenues if it can be demonstrated by the infringer that they have increased as a result of the recognition of infringing revenues – i.e. allocable indirect costs. Costs which did not increase as a result of the recognition of infringing revenues may not be attributable to infringing revenues, as they would have been incurred whether or not the infringed revenues were generated. Considering the materiality of the infringing revenues relative to the total revenues of the infringer may indicate whether any of the infringer’s costs – other than direct costs – are attributable to the infringing revenues. For example, if the infringing revenues are $1 million per year, and the infringer’s total revenues are $1 billion per year, it is unlikely that the infringer’s fixed and administrative costs are uniquely attributable to the infringing revenues.

Evidence

The financial expert can also assist counsel in identifying the information required for quantifying lost profits. Both the litigator and financial expert should be sensitive to using information reflecting actual revenues and costs – not those estimated, forecasted, or budgeted – and should attempt to test or verify the purported revenue and cost amounts. For example, mere spreadsheets and other computer data prepared or maintained by the infringer purporting to report infringing revenues and costs should be supported by sound evidence. While the infringer will typically not be required to produce information it does not maintain in the ordinary course of business, the litigator should be aware that an experienced financial expert could easily identify several sources of information which could serve as sound evidence of the existence and magnitude of the infringer’s actual revenues and costs.

Early Retention

To address some of the above challenges, consulting with the financial expert at the outset of the litigation – including during the drafting of the pleadings – should make discovery more efficient and enhance the effectiveness of the profitability analysis. The financial expert can gauge the economic reality of the claim, can assist in the clear and concise preparation of information requests, and can assist in promptly evaluating and responding to production of quantitative and qualitative information pertinent to pleading and ultimately proving damages. Another consideration is that a competent financial expert “speaks the same language” as the client’s financial staff, and can serve as a key liaison between counsel and their client during any stage of the dispute.

Conclusion

As counsel’s guide through unfamiliar territory, the financial expert adds value to the litigation by providing actual and apparent credibility, independence, and objectivity; providing litigation-related experience, expertise, and training coupled with industry, business, and financial acumen; and allowing for a liaison with the client’s financial staff, thus, facilitating easy access to a “reality check” for analyses, methods, and techniques contemplated by the client during the course of the litigation.

1 Roman Matatov is a member of Marcum’s Advisory Services group in New York City and specializes in intellectual property and commercial disputes, and intellectual property valuation. Roman presides over the Manhattan/Bronx Chapter of the NYS Society of CPAs and the New York City Chapter of the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners. Roman has also taught Principles of Forensic Accounting to Baruch College’s MBA students since 2008.