Challenges in the Valuation of Hedge Funds: Part I

By Vladimir V. Korobov CPA, ABV, ASA, Partner, Valuation and Litigation Support Services

It would not come as a surprise to our readers that most, if not all, hedge fund managers consider themselves better-than-average spotters of value and pickers of winning investments. Many of them, however, are not as confident when it comes to ascribing value to their own firms. This is understandable because the proper valuation of a hedge fund firm almost always comes with significant challenges related to the complexities of the firm’s operating structure and the unique valuation issues. To successfully tackle these challenges, the valuation specialist must have the necessary expertise. This article is the first in a series of essays that will discuss various aspects of valuing a hedge fund management firm.

Typical Requested Valuation Areas

Traditional areas of valuation related to hedge funds include tax, litigation, and transactions. Tax valuations are frequently sought in the context of transferring an interest in a management entity, general partner entity, or an investment fund as part of estate planning,1 employees’ compensation, and restructuring. An example of litigation-related valuation is valuation performed for matrimonial purposes. As the industry continues to recover from the 2008-2009 credit crisis, a re-emergence of institutional investors willing to invest in minority stakes in hedge fund management companies has increased the need for transactional valuation advice. This renewed institutional investment appetite has also created a need for valuing the minority investments in hedge fund managers for financial reporting purposes.

Organizational Structure and its Impact on Valuation Analysis

Organizationally, hedge fund firms typically operate through either a single entity that acts as both investment manager and general partner of investments, or a structure in which the investment manager and general partner roles are separated and given to different entities. The choice of organizational structure affects valuation analysis in several important ways.

When the management company and the general partner are a single entity, first, the management company has two revenue/cash flow streams – management and performance fees; and second, this combination of revenue/cash flow streams with different risk profiles necessitates the development of a discount rate that properly considers the risk attributes of each revenue/cash flow stream.

In the structure that separates management and general partner roles, the management company receives management fees, while the general partner entity receives performance fees. The impact of this structure on the valuation analysis, first, is found in the homogenous nature of the entities’ respective revenue/cash flow streams, which warrant the development of separate discount rates; second, raises a need to address reasonable compensation in each cash flow stream; and third, creates a potential issue with an allocation of terminal value (if the terminal value is found to be appropriate).

Operating Terms and Their Impact on Valuation Analysis

Historically, hedge funds measured their investment performance in terms of an absolute return. Increasingly, however, investors demand that hedge fund managers measure their investment performance relative to a pre-determined benchmark.2

From the valuation perspective, the effect of the difference is two-fold. First, all else being equal, measuring performance against a benchmark arguably increases the risk of performance fees, because it makes it harder for the manager to earn them. Second, it reduces the aggregate amount of performance fees that the manager receives, because a smaller portion of the capital appreciation is subject to performance fees.

While discussing a hedge fund’s performance, it is important to note that performance is usually subject to a “high-water mark.” Therefore, the valuation analysis needs to consider the fund’s overall high-water mark status as of the valuation date.

Unlike private equity or venture capital funds, hedge funds do not typically have contractual limits on their lives. However, in a valuation context, this does not mean that hedge funds should be automatically presumed to have perpetual life spans, like traditional businesses. The hedge funds’ longevity depends on many factors. Examples of these factors include:

- A manager’s investment skills and ability to achieve consistent performance.

- Age and intentions of the firm’s principals, and their ability and willingness to transition duties to others within an organization (i.e., “key persons” risk).

- The size of the assets under management (“AUM”).

- The nature and diversity of the fund’s investor base.

Therefore, an assumption of perpetual operation often needs to be explicitly evaluated in every case.

Consideration of Valuation Methodologies

Readers are undoubtedly familiar with the three traditional methodologies to value an investment – an income approach, a market approach, and an asset – or cost – approach. The premise of the income approach is that the value of an investment equals the present value of the expected cash flows, and a common application of this approach is the discounted cash flow – or DCF – method. The premise of the market approach is that quoted prices of similar securities traded on exchanges and other organized markets, or prices at which similar securities have been sold in private transactions, can provide an indication of value for an investment. And finally, the asset approach effectively seeks to establish a replacement value for an investment.

Generally, the market approach is poorly suited for valuing hedge funds. This is because the existing publicly traded alternative asset management firms typically manage multiple funds that invest across many asset classes and investment strategies. A typical privately held hedge fund firm, on the other hand, lacks such diversification and a large asset base. Furthermore, unlike their publicly traded counterparts, private hedge fund firms usually have “key person” issues, i.e., their success depends significantly on their “star” founders/portfolio managers. Finally, sufficient information about the acquired hedge fund firms is rarely, if ever, disclosed to determine meaningful acquisition multiples.3

The asset approach is generally not appropriate for valuing profitable, operating companies.4 Thus, the income approach – specifically, the DCF method – is the preferred and, often, only viable valuation technique.5 The DCF method can be significantly enhanced by simulation techniques, such as Monte Carlo.

Developing a DCF Analysis

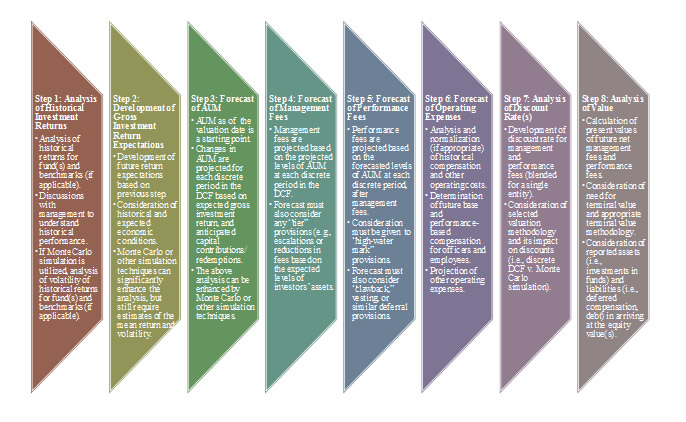

The diagram below summarizes the analytical steps typically considered in the valuation of a hedge fund using the DCF method.

As can be seen from this diagram, an analysis of the future levels of AUM is a critical component of valuation, because AUM is the key value-driver that determines the future cash flow. Monte Carlo simulation can significantly enhance development of the AUM forecast, as it allows for modeling future investment returns and investor behavior (i.e., capital contributions and redemptions).

Challenges and Issues under the Income Approach

Hedge funds present a number of unique valuation challenges. In this article, we will focus on one such issue – a determination of reasonable compensation for the firm’s principals.

Reasonable Compensation for Principals

We can already anticipate some readers’ opinions on this subject. After all, what managers earn from the assets under their firms’ management is a function of the managers’ ability for, and success in, delivering a strong and consistent performance on a risk-adjusted basis. Therefore, shouldn’t what managers take from their firms represent reasonable and market-based compensation for their skills? The answer to this question is not so obvious. Compensation of hedge fund principals can be thought of as having two components: (1) market compensation for a given level of responsibility; and (2) a return on an owner’s equity investment. Since an ultimate goal of any valuation is to establish in monetary terms the present value of the second component, a proper bifurcation of the two compensation components becomes important and necessary.

In the valuation context, compensation of principals in hedge fund management first presents issues that are similar to those in traditional closely held businesses. Some examples of these issues:

- Principals’ primary compensation often comes in the form of profit distributions, rather than traditional salaries and bonuses.

- When principals do receive traditional compensation, it reflects the fact that these individuals are often “star” contributors, “faces” of the firms, and primary investment idea- generators, without whom the business would not be viable.

- Principals often play multiple roles in the business, including those of portfolio managers, chief investment officers, and chief executive officers.

Thus, a normalization of reported compensation may be necessary, even when the subject of valuation is a minority interest.6

Due to the competitive nature of the industry, a practical challenge that valuation specialists face is access to reliable compensation benchmarking data. In this context, valuation practitioners essentially have one or more of the following options:

- A review of compensation of non-owner portfolio managers and officers of the subject hedge fund;

- A review of the published industry-specific compensation surveys; and

- An analysis of the aggregate relative compensation levels reported by the publicly traded firms.

Some thoughts on these options are presented below.

Review of Compensation of Non-Owner Officers. A review of the compensation of non-owner officers and portfolio managers of the subject hedge fund is a logical step. Hedge funds compete fiercely for talent, and not only with each other, but also with broader investment management and financial services industry participants (for example, investment banks). Therefore, in the absence of evidence to the contrary, compensation paid to non-owner officers and portfolio managers can generally be considered a reasonable proxy for market compensation for a given officer position or staffing level within the firm. The valuation specialist can then use this information as a basis for determining reasonable compensation for the principals of the firm, after giving proper consideration to the differences between the functional roles that the principals and non-owner officers and managers have in the firm.

Review of Published Industry-Specific Compensation Surveys. There are a number of published compensation surveys/reports for the hedge fund industry. Examples include Glocap Hedge Fund Compensation Report published by HFR, Inc.7 and Hedge Fund Compensation Report published by Benchmark Compensation.8 Updated periodically, the reports provide general guidelines to the compensation structures in the hedge fund industry by position type, fund size, and performance, and other metrics. These studies can be valuable in the analysis of reasonable compensation levels for the firm’s principals.9 When relying on these reports, however, the valuation specialists should be aware that, like other studies involving hedge funds, the underlying data may have reporting and selection biases.

Analysis of Aggregate Compensation Levels Reported by Publicly Traded Firms. Although it was stated earlier that the market approach is poorly suited for valuing hedge funds, an analysis of relevant financial information, such as the total relative compensation levels, of the publicly traded alternative investment management and investment banking firms can provide useful insights. Public companies constantly try to balance the competing needs of various stakeholders, e.g., employees and shareholders; thus, the reported levels of total compensation in the industry – and especially their trend over time – may provide an indication of a point of equilibrium between the companies’ need to attract highly talented employees and the stockholders’ demand for a fair rate of return on their investment. Thus, reasonable compensation of principals of the subject hedge fund can be estimated as the target total compensation based on the aggregate relative compensation levels of the public companies, less the actual compensation that the subject firm pays to its non-owner employees. While conceptually intuitive, this analytical approach presents some practical challenges. Valuation specialists should exercise special care in analyzing the public companies’ financial information, as there is a divergence of reporting practices among the firms, particularly with respect to performance fees.

Conclusion

This discussion is not intended as, nor can it be, a treatise on hedge fund valuation. Rather, the goal is to provide the reader with thoughts on and ideas about some issues that frequently arise in the valuation of hedge funds. The hedge fund structure and operating terms form a framework for the analysis and influence key valuation inputs. The DCF method is the preferred, and most often the only viable, valuation technique for hedge funds. In applying the DCF method, the valuation specialist should keep in mind that AUM and the fund’s fee structure are the key value-drivers. Determination of reasonable compensation for founders/owners is one of the challenges in valuing hedge funds. Ignorance of or failure to consider the aforementioned issues often leads to erroneous valuation conclusions.

About the Author

Vladimir V. Korobov, CPA, ABV, ASA, is a partner at Marcum LLP in the Valuation and Litigation Support Services group. He has more than 20 years of experience providing business valuation, litigation support, and advisory services with a focus on alternative and traditional asset management, and financial institutions.

Resources

1. In the estate planning and gift tax compliance context, a transfer can be an actual transfer of legal ownership of an interest, or a constructive transfer of the economics of ownership through a synthetic derivative, such as a carry derivative contract.

2.Examples of frequently used benchmarks include performance of the S&P 500 index, a total return of a specific U.S. Treasury security, or even an excess return measure, such as the Sharp ratio.

3. This issue is particularly relevant when a valuation is performed for litigation purposes. While some valuation specialists and investment banking firms may have access to proprietary transactional information by virtue of their work with the hedge funds, this information can rarely, if ever, be credibly used in litigation without disclosing the confidential client information.

4. While the asset approach is generally not appropriate for valuing interests in management companies, or determining the present value of future performance fees, it may be used to value limited partnership interests in the investment funds or equity interests in general partner entities (especially if the principals of the firm have significant investments in the funds through the general partner entities).

5. Some valuation specialists attempt to value hedge funds using the capitalization of cash flow method, rather than the DCF. This most often happens in litigation. The specialists justify their selection of this method by arguing that its simplicity makes it more understandable for a judge. In general, a capitalization of cash flow method is a valid valuation technique that has merits in certain circumstances. The critical assumptions of this method are that (1) the business has a perpetual life; and (2) the cash flow grows at a sustainable long-term rate, which is generally considered to approximate the rate of inflation. The seeming simplicity of this method and its underlying assumptions, however, is what makes this method completely inappropriate for valuing hedge funds.

6. A normalization of principals’ compensation is generally considered a control-level adjustment, because it implies that a holder of the subject interest has control over management’s compensation, and thus can enhance the firm’s cash flow. Therefore, when a subject of valuation is a non-controlling interest, it is important to consider and properly select a discount for lack of control. Unfortunately, all too often valuation specialists fail to properly evaluate the characteristics of the subject interest and apply an appropriate discount for lack of control in these circumstances.

7. www.hedgefundresearch.com/hfr-industry-reports, Reports, © 2018 Hedge Fund Research, Inc. – All rights reserved.

8. www.hedgefundcompensationreport.com, Hedge Fund Compensation Report, © Copyright 2016 Benchmark Compensation.

9. As was mentioned earlier, proper consideration should be given to the differences in functional roles that the principals and non-owner officers/managers have in the firm.